Revised 15 March 2013

Risk Factors

The vast majority of lung cancers (85–90%) are associated with cigarette smoking. Preventing the onset of smoking and bringing about successful smoking cessation in current smokers will most effectively achieve primary prevention of lung cancer. Pooled evidence comparing non-smokers living with smokers indicates that second-hand smoke is associated with a 20–30% increased risk in lung cancer, after controlling for some potential biases and confounding factors.

Other risk factors for lung cancer, predominantly environmental and occupational, include exposure to radon indoors, air pollution, arsenic, asbestos, silica, chromates, chloromethyl ethers, nickel, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and radon decay products. In addition, fumes from cooking stoves and biomass fires are associated with increased risk in some developing countries. Patients with head and neck cancer (excluding nasopharyngeal carcinoma) and patients with non-small cell lung cancer are at risk of developing second primary cancer in the lung because of field carcinogenesis.

A family history of lung cancer has been frequently found to be associated with lung cancer even after careful adjustment for smoking. Genome-wide association studies have identified inherited susceptibility variants for lung cancer on several chromosomal loci such as15q25 (nicotinic

acetylcholine receptor subunit CHRNA5) and 6q23-25. Several additional factors have been associated with lung cancer, but the findings have not been consistent. For example, several studies have suggested that diets rich in fruits and vegetables are protective. In general, the associations between non-smoking factors and lung cancer are substantially smaller than the association between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. However, it should be noted that even if all tobacco smoke induced lung cancers were eliminated, lung cancer would still be the 6th most common cause of cancer deaths.

Prevention

Cessation of cigarette smoking would clearly prevent the majority of lung cancer. Secondary prevention by pharmacological treatment to reverse a recognizable premalignant lesion is under investigation at the British Columbia Cancer Agency. A standard approach does not exist at this time.

Tobacco Control

Lung cancer is largely preventable as 85% of all cases are related to smoking. For children and adolescents, the focus should be on not starting smoking, whereas for adults, smoking cessation is an effective method of reducing lung cancer risk.

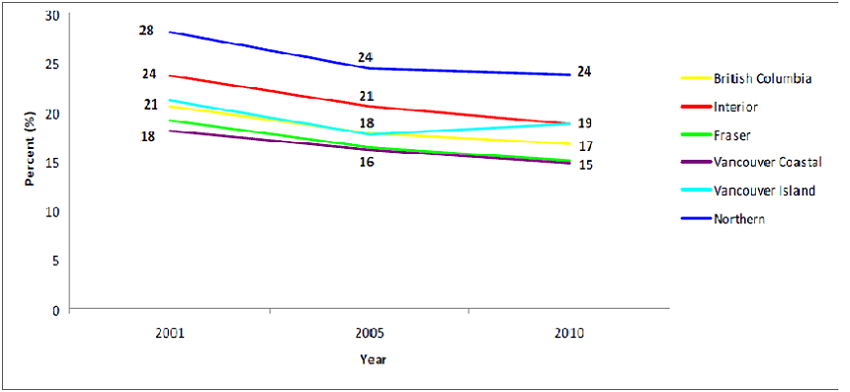

Over the past decade there has been an overall decline in the proportion of Canadians over age 12 who smokes (from 25% to 17%) with the lowest rate in British Columbia although rates for women have levelled off (stopped declining) since 2006. The Northern Health Region has consistently higher smoking rates than other health regions in BC and not surprising the poorest lung cancer outcome.

Percentage of Population (age ≥ 12) who Reported Smoking Cigarettes Every Day, Over Time by Health Regions

Physicians and other health care professionals can help to reduce cigarette smoking and lung cancer in the following ways.

a) | Set an example by not smoking.

|

b) | Display and promote "anti-smoking" information. |

c) | Take a careful smoking history on all patients and counsel smoking patients to stop even if they are well. Physician counseling is one of the most effective interventions. |

d) | Be familiar with the methods and pharmacology of nicotine replacement therapies, Bupropion (Zyban) and Varenicline (Champix) as an adjunct to counseling. |

e) | Inform the patient how to access government subsidy for smoking cessation drugs by phoning HealthLink BC at 8-1-1 to register for the BC Smoking Cessation Program. Patients have a choice of obtaining nicotine patches or gum through a community pharmacy or through direct mail distribution from the government. Bupropion and varenicline up to 12 weeks are covered under Fair PharmaCare, and Plans B, C and G |

f) | Be aware of the non-smoking advice and programs available through the Canadian Cancer Society, British Columbia Lung Association and the British Columbia Medical Association. (http://www.lung.ca) |

g) | Assist those who are promoting legislation to restrict all cigarette advertising and increase tobacco taxes. |

h) | Be aware of industrial and environmental hazards, which may be related to lung cancer. |

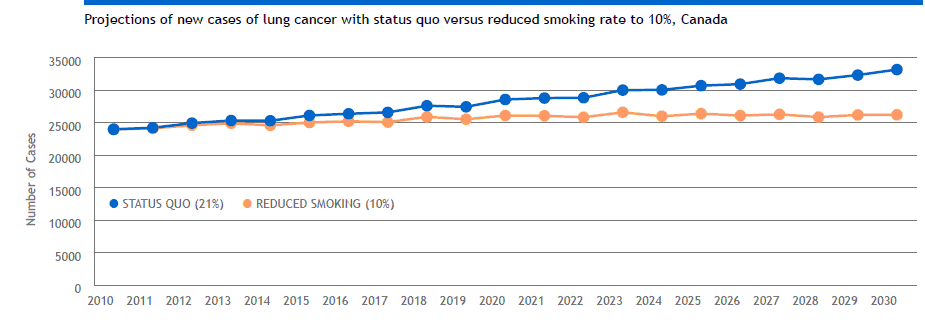

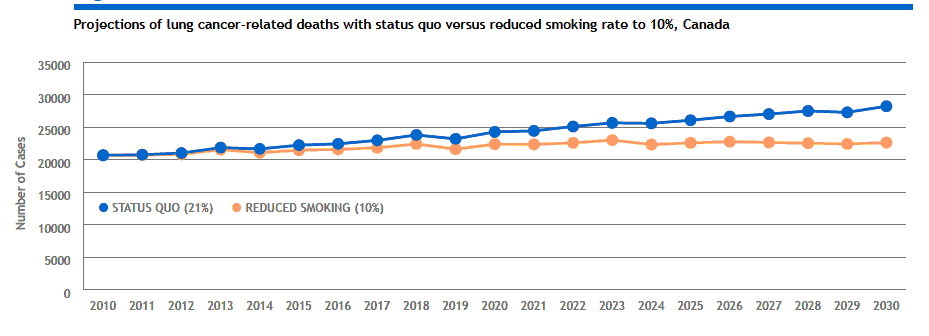

The Cancer Risk Management Model developed by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer shows that if Canadian smoking rates dropped from 21% to 10%, by 2030 an estimated 58,000 new cases of lung cancer could be avoided.

As well, an estimated 46,000 deaths from lung cancer could be avoided in Canada. These projections point to the importance of tobacco control in reducing the societal burden due to lung cancer.

Key References:

- Canadian Cancer Society/National Cancer Institute of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2011. Toronto, ON: CCS/NCIC; 2011

- World Health Organization. Research for international tobacco control. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER package. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008.

- Surveillance and Risk Assessment Division, CCDPC, Public Health Agency of Canada; Statistics Canada; Canadian Council of Cancer Registries. Cancer surveillance on-line. Available from: http://dsol-smed.phac-aspc.gc.ca/dsol-smed/.

- Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, et al. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet. 2011;377(9760):127–38.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2006.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2004. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol. 83.

Tammemagi MC, Pinsky PF, Caporaso NE, et al. Lung cancer risk prediction – prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer screening trial models and validation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(13):1058-68.

Hung RJ, McKay JD, Gaborieau V, et al. A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature. 2008;452(7187):633–7.

Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, Gorlov IP, Gu J, Eisen T, et al. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):616–22.

Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Sulem P, et al. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature. 2008;452(7187):638–42.

Bailey- Wilson JE, Amos CI, Pinney SM, Petersen GM, de Andrade M, Wiest JS, et al. A major lung cancer susceptibility locus maps to chromosome 6q23-25. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(3):460-74.