Presentation

- GISTs are the most common STs of the GI tract, and can arise anywhere in the GI tract, but stomach (60%) and small intestine (30%) are the most common primary sites. Other much less common sites include duodenum, rectum, colon, appendix and rarely, esophagus.

- Presenting symptoms include early satiety, abdominal pain, intraperitoneal hemorrhage, GI bleeding, or fatigue related to anemia.

- Some patients may present with an acute abdomen due to rupture or obstruction. Up to 20% of patients have overt metastases at diagnosis, typically within the abdominal cavity or liver.

- Lymph node metastases are rare except when arising in pediatric GISTs, pediatric-type GISTs in young adults and syndromic GISTs.

- Lung and extra-abdominal disease are seen usually in advanced disease.

- Most GISTs are sporadic.

- Rare tumour syndromes predisposing to GIST include: neurofibromatosis 1, Carney-Stratakis syndrome and Carney triad.

Imaging

- Contrast-enhanced CT is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis, initial staging, restaging, monitoring response to therapy and surveillance.

- PET scan helps to differentiate active tumour from necrotic, inactive scar or benign tissue, and can be used to clarify ambiguous findings on CT or MRI scans, but it is not a substitute for CT.

Biopsy

- GISTs are soft and fragile tumours mostly arising from the muscularis propria and sometimes muscularis mucosa, seen as smooth submucosal masses.

- Endoscopic biopsies using standard techniques usually do not obtain sufficient tissue for a definite diagnosis.

- Pre-operative biopsy is not generally recommended for a resectable lesion in which there is a high suspicion for GIST and the patient is otherwise operable.

- EUS-guided FNA biopsy of primary site is preferred over percutaneous biopsy due to the risk of tumour hemorrhage and intra-abdominal tumour dissemination.

- Biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of primary GIST before initiating preoperative therapy.

- Percutaneous image-guided biopsy may be appropriate for confirmation of metastatic disease.

Pathologic assessment

- Pathology report should include: anatomic location, size, mitotic rate.

- GISTs arise most commonly from KIT and PDGFRA activating mutations.

- Mutation analysis of KIT and PDGFRA is mandatory for optimal care of GIST.

- Most GISTs express KIT (CD117) and DOG1.

- Approximately 80% of GISTs have a mutation in the gene encoding the KIT tyrosine receptor kinase; another 5-10% have a mutation in the gene encoding the PDGFRA receptor tyrosine kinase.

- About 10-15% are wild-type with no detectable KIT or PDGRFA mutations.

- Most KIT mutations occur in exon 11 (90%) or exon 9 (8%). Other rare KIT mutations are found in exon 13 and exon 17.

- PDGFRA mutations usually affect exons 12,14 and 18.

- KIT exon 11 mutations are common in GISTs of all sites, whereas KIT exon 9 mutations are specific for intestinal GISTs. PDGFRA exon 18 mutations are common in gastric GISTs.

- Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for CD117, DOG1 and /or CD34 and molecular genetic testing to identify KIT and/or PDGFRA mutations are important in the diagnosis of GIST.

- However, the absence of KIT and/or PDGFRA does not exclude GIST.

- Tumours lacking KIT or PDGFRA mutations should be considered for further evaluation with SDHB immunostaining, BRAF mutation analysis and SDH gene mutation analysis.

- Loss-of-function mutations in succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) gene subunits or loss of SDHB protein expression by IHC have been identified in a majority of wild-type GISTs lacking KIT ad PDGFRA mutations.

- SDH-deficient tumours should prompt germline testing for SDH mutations. Carney-Stratakis syndrome is a rare heritable condition with a germline mutation in SDH complex genes SDHA, SDHB, SDHC or SDHD.

- Cancer genetics Solid tumour requisition (PDF)

Prognostic and Predictive factors

- Tumour size

- Location of primary

- Mitotic rate

- Tumour rupture

- Incomplete resection

- The presence of KIT or PDGFRA mutation status are predictive of response to TKI therapy in patients with advanced or metastatic GIST. Conversely, GISTs that do not contain KIT or PDGFRA mutations are unlikely to benefit from imatinib therapy. GISTS harbouring the PDGFRA mutation D842V (about 8% of G ISTs) do not respond to imatinib or other approved Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), but most respond to BLU-285.

- SDH-deficient and NF-1 –related GISTs are less sensitive to TKIs.

- Factors associated with poorer DFS include: KIT exon 9 duplication, KIT exon 11 deletion, non-gastric primary site, larger tumour size, and high mitotic index.

Risk stratification

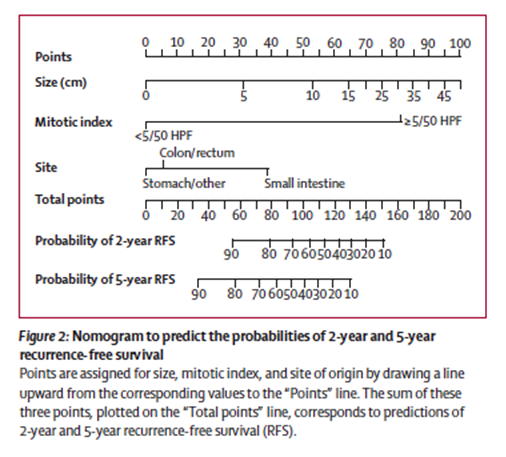

Nomogram to predict probabilities of 2- and 5-year recurrence-free survival

- Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Center calculator tool to predict 2 and 5 year recurrence free survival after surgery for GIST

Surgery

- GISTs are fragile and should be handled with care to avoid tumour rupture.

- Surgery is the primary treatment for localized and potentially resectable GIST lesions with a goal of complete gross resection with intact pseudocapsule.

- Lymph node dissection is usually not indicated in adults.

- All localized GISTs >= 2cm should be resected.

- Management of smaller gastric GISTs <2cm should be individualized.

Neoadjuvant therapy

- Preoperative therapy with imatinib, an inhibitor of KIT and PDGFRA, can be considered in patients with unresectable or borderline resectable locally advanced tumour, or a potentially resectable tumour that requires extensive organ disruption.

- In patients with GIST arising in the esophagus, esophagogastric junction, duodenum or distal rectum, preoperative imatinib may shrink the tumour to allow a more conservative excision and increase the likelihood of a complete (R0) surgical resection.

- Typically neoadjuvant imatinib is administered for 6-12 months, with frequent imaging and periodic surgical re-assessment to determine when to operate (ie, at first resectability versus best tumour response).

- Patients whose tumours are known to be unresponsive to imatinib eg. PDGFRA D842V mutation or SDH-deficient or Neurofibromatosis (NF-1) related GIST should proceed directly to surgery.

- The usual dose of imatinib is 400 mg daily.

Adjuvant therapy

- Imatinib is a selective inhibitor of the KIT protein tyrosine kinase.

- The optimum duration of post-operative adjuvant therapy is not yet established.

- Based on the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG) XVIII trial, the current standard is to treat patients with high risk GIST for 3 years postoperatively at a dose of imatinib 400 mg once daily.

- At the BC Cancer centres provincially, patients with nomogram scores of 80 or higher (estimated 5 year RFS 65% or less) are considered high risk and are offered adjuvant Imatinib for 3 years.

- Tumours with exon 9 mutation are less sensitive to Imatinib, but in the adjuvant setting it is unknown whether a higher dose of 800mg imatinib daily would be beneficial. This will require further prospective study.

NCCN guidelines:

- For completely resected GIST:

- History and physical exam every 3-6 months for 5 years then annually.

- CT scan every 3-6 months for 3-5 years, then annually.

ESMO guidelines:

- Very low risk GIST: routine follow-up likely not warranted although recurrence risk is not nil.

- Low-risk GIST: benefit of routine follow-up is unknown. Could consider CT or MRI every 6-12 months for 5 years.

- High risk GST: CT or MRI every 3 -6 months for 3 years during adjuvant therapy, then imaging every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months until 5 years from stopping adjuvant imatinib, then annually for another 5 years.

Diagnosis

- Baseline imaging is recommended prior to initiation of treatment.

- Patients with unresectable or widely metastatic disease should have diagnosis confirmed with biopsy.

Imatinib

- Most GISTs are characterized by activating mutations in the KIT or PDGFRA proto-oncogenes affecting membrane tyrosine kinase (TK) receptors.

- Systemic therapy in the form of small molecules targeting receptor tyrosine kinases (tyrosine kinase inhibitors or TKI) have induced rapid and sustained clinical benefit in GISTs.

- Imatinib is the primary treatment for patients with advanced, unresectable or metastatic GIST at a standard does of 400mg daily.

- If there is poor response or tumour progression on 400 mg daily then imatinib should be escalated to 800 mg daily (given as 400 mg twice daily).

- Poor initial response to imatinib at 400 mg daily is more frequent in patients with exon 9 mutations. These patients should be closely observed and dose escalated quickly.

- Continuous use of imatinib is recommended for metastatic GIST until progression.

- Common side-effects of imatinib include edema, diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, muscle cramps, abdominal pain and rash.

- Serious side effects such as lever enzyme abnormalities, lung toxicity, low blood counts and GI bleeding have rarely been reported and often improve after imatinib is withheld.

- The side-effect profile may improve with prolonged therapy.

- Imatinib is a rare of cardiotoxicity such as congestive heart failure, arrhythmias or acute coronary syndromes, occurring in less than 1% of treated patients.

Sunitinib

- Sunitinib is a multi-targeted TKI with activity against KIT, PDGFR, VEGFR, and FLT-1/KDR.

- Second-line therapy with Sunitinib should be initiated when the majority of disease is no longer controlled on imatinib.

- The usual dose of sunitinib is 50 mg daily for 28 days with 14 off in a 42-day cycle.

- To avoid recurrent tumour symptoms during the 2 week break and to manage adverse effects, it would not be unreasonable to use a continuous daily dose of 37.5 mg, which provides similar safety, tolerability and response rates to the 4 weeks on/2 weeks off regimen.

- Sunitinib-related toxicities can often be managed with dose interruptions or reductions.

- Side effects include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, cytopenias, diarrhea, abdominal pain, mucositis, anorexia, skin discoloration and hypertension.

- Sunitinib is associated with cardiotoxicity and hypothyroidism. Therefore patients should be closely monitored for hypertension, LVEF and TSH.

- If hypothyroidism is detected, patients should receive thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

- Hypertension should be treated with antihypertensive agents.

Regorafenib

- Regorafenib is a multi-targeted TKI targeting VEGFRI-3, TEK, KIT, RET, RAF1,BRAF, PDGFR and FGFR.

- Regorafenib has been approved for treatment of patients with GIST previously treated with imatinib and sunitinib.

- The dose is 160 mg daily for 21 days with 7 days off, repeated every 28 days.

- The phase 3 GIST-Regorafenib in progressive disease (GRID) trial demonstrated 4 month improvement in PFS but no difference in OS (probably due to cross-over).

Surgical management of advanced /metastatic GIST

- The role of metastasectomy in patients whose disease is controlled with imatinib is controversial.

- It is possible that debulking of metastatic disease after an initial stabilization or response to imatinib may help in prolonging disease control by preventing the emergence of resistant clones.

- Resection of a focal progressing lesion may allow the use imatinib to be prolonged, whereas surgery for diffuse progression would not.

- The role of metastasis surgery in patients on sunitinib or regorafenib is unclear, except for patients who require emergency surgery. Patients with progressive disease on sunitinib and regorafenib likely have multiple resistant clones and greater tumour bulk , and therefore the potential benefits versus risks of surgery need to be carefully considered.

Other palliative approaches

- Radiotherapy can be effective in stabilizing progressing liver or intra-abdominal lesions.

- Local interventional modalities such as embolization and radiofrequency ablation can potentially be considered for liver metastases.

- For patients with progressive GIST after all standard therapies, discontinuing TKI therapy is not recommended given the rapid rate of progression documented after discontinuation.

- Restarting imatinib after progression on at least prior imatinib and sunitinib increased PFS slightly form 0.9-1.8 months compared with best supportive care.

- Pazopanib plus best supportive care was shown to improve PFS compared to best supportive care alone, in a small randomized trial of patients whose GIST was resistant to imatinib and sunitinib.

References

- Von Mehren M, Joensuu H. Gastrointestinal stroma tumors. JCO 2018; 36(2):136-43.

- Gold J, Gonen M, Gutierrez A, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for recurrence-free survival after complete surgical resection of localized primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor: retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10:1045-52

- Wozniak A, Rutkowski P, Schoffski P, et al. Tumor genotype is an independent prognostic factor in primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors of gastric origin: a European multicenter analysis based on ConticaGIST. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:6105-6116.

- Rose S. BLU-285, DCC-2618 show activity against GIST. Cancer Discov 2017; 7:121-122.

- Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. One versus three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA 2012; 307 (12):1265-72

- Demetri G, van Oosteram AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor after failure of imatinib: A randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2006;368:1329-1338

- George S, Blay JY, Casali OPG, et al. Clinical evaluation of continuous daily dosing of sunitinib malate in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor after imatinib failure. Eur J Caner 2009; 45:1959-1968.

- Demetri GD, Reichardt P, Kang YK, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): An international, multicenter, randomized , placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013; 381:295-302.

- Du CY, Zhou Y, Song C, et al. Is there a role of surgery in patients with recurrent or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors responding to imatinib: A prospective randomized trial in China. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50: 1772-1778.

- Bauer S, Rutkowski P, Hohenberger P, et al. Long-term followup of patients with GIST undergoing metastectomy in the era of imatinib: Analysis of prognostic factors (EORTC-STBSG collaborative study). Eur J Surg Oncol 2014;40:412-419.

- Kang YK, Ryu MH, Yoo C, et al. Resumption of imatinib to control metastatic or unresectable gastrointestinal stromal tumors after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (RIGHT): A randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14:1175-1182.

- Mir O, Cropet C, Toulemonde M, et al. Pazopanib plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors resistant to imatinib and sunitinib (PAZOGIST): A randomized, multicentre, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:632-641

- Trent C, Patel SS, Zhang J, et al. Cancer 2010;116(1):184-92.